The roots of Turkish tiles and ceramics date back to the 8th and 9th centuries, when the Uyghurs, along with the Seljuks, brought their influence to Anatolia. The city of İznik was the most active centre and a technically advanced area, receiving designs from Ottoman court artists for completion and then sending them back to the palace. Compared to ceramic production elsewhere in the Middle East, Iznik tiles were made from a quartz-based composite rather than heavy clay. Formed from this mineral mixture, the body was coated with a thin layer of slip to provide a radiant white background. Patterns provided by the imperial atelier were then drawn on the tiles using perforated stencils, after which they were painted in various colours. Finally, a glaze was applied to fix the design.

The roots of Turkish tiles and ceramics date back to the 8th and 9th centuries, when the Uyghurs, along with the Seljuks, brought their influence to Anatolia. The city of İznik was the most active centre and a technically advanced area, receiving designs from Ottoman court artists for completion and then sending them back to the palace. Compared to ceramic production elsewhere in the Middle East, Iznik tiles were made from a quartz-based composite rather than heavy clay. Formed from this mineral mixture, the body was coated with a thin layer of slip to provide a radiant white background. Patterns provided by the imperial atelier were then drawn on the tiles using perforated stencils, after which they were painted in various colours. Finally, a glaze was applied to fix the design.

The flourishing of art

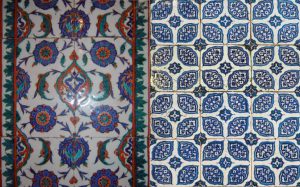

The flourishing of artAt the end of the 15th century came a new era of Ottoman ceramic art. Sultan Mehmed II held art in high esteem, increasing court patronage in many artistic fields and spurring innovation in various media. This resulted in consistency of theme and motif in everything from embroidered textiles to metalwork, and tile art was no exception. İznik ceramics were often official gifts from Ottoman leaders to foreign dignitaries, while İznik tiles were used to decorate palaces, mosques and other important structures. When Süleyman the Magnificent began his reign in 1520, the quality of ceramics increased significantly, new designs began to develop and the tile art form was approaching its zenith. The Ottoman Empire was entering its richest period, both politically and culturally. With the proliferation of buildings and the peak of tile production, motifs shifted towards a more naturalistic and free style. Tulips, carnations, hyacinths, roses, spring flowers, lilies, cypresses, grape clusters and vine leaves appeared in free and experimental compositions, rich in their overall visual spectacle. Towards the end of the 16th century the motifs also extended to themes from everyday life. Tiles were covered with patterns of boats, architecture and even human and animal figures. Depictions of birds, for example, proliferated - reflecting Ottoman society's high regard for these creatures and their religious overtones. Religious inscriptions also found their way onto Iznik wares, and the Süleymaniye Mosque was the first significant example of tiles being used as a medium for Arabic inscriptions in 1557. Beautiful tiles from İznik appeared in the Süleymaniye Mosque (1557), the tomb of Sultan Hürrem (1558), the Rüştem Paşa Mosque (1561), the tomb of Süleyman I (1566), the Sokullu Mehmed Paşa Mosque (1572), the Piyale Paşa Mosque (1573) and the Valide Atik Mosque (1583), among others.

Decline of art

Decline of artFrom the end of the 16th century, tensions began to emerge between the Iznice potters and the imperial court. Tile makers devoted more and more energy to fulfilling orders from wealthy private individuals, who often came from Europe. Ottoman officials responded by issuing edicts that prohibited potters from accepting other work before finalising orders for the empire. However, tile makers were reluctant to comply. At a time when inflation was wreaking havoc due to the empire's economic troubles, Ottoman officials refused to adjust tile prices accordingly. Such disputes with the court - combined with natural disasters and spreading disease - led to a decline in the quality of Iznik production in the early 17th century. Innovation in design was just as strong, but technical standards fell sharply. Flaws and imperfections in glaze work began to appear, and colours intermingled. By the end of the 17th century, production in Iznik came to an end. In the 18th century the ceramic industry almost completely disappeared and Kütahya became its leading centre.

Contemporary

ContemporaryToday, Kütahya is experiencing a revival as a centre of tile and ceramic production, with private workshops and educational institutions in İznik, Istanbul and Bursa working to maintain the İznik tile tradition in the face of modernity. Artists such as Adnan Ergüler, Elif Uras, Tahir Eğinci and Faik Kırımlı are trying to reinvent the magic of tiles.